When the Strait came to a halt

How Chinese military drills in the Taiwan Strait disrupted shipping traffic on one of the world's major trade lanes

By Federico Acosta Rainis

On 2 August, Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, landed in Taiwan on an official visit. Second in the presidential line of succession, she is the highest-ranking US official to visit the island since 1997.

The visit increased tensions between Washington and Beijing. Taiwan is a democracy recognised by only 13 countries around the world; China considers it a rebel province of its territory and has repeatedly claimed that it will take it back even through the use of force.

In retaliation to Pelosi's trip, Xi Jinping's government launched a week-long series of military drills around the island.

An analysis of radar satellite images processed by artificial intelligence shows that after the start of the exercises, the number of large ships such as container ships, bulk carriers and tankers decreased by more than 50% in the international waters of the Strait.

That is a very significant hit on a busy world trade route.

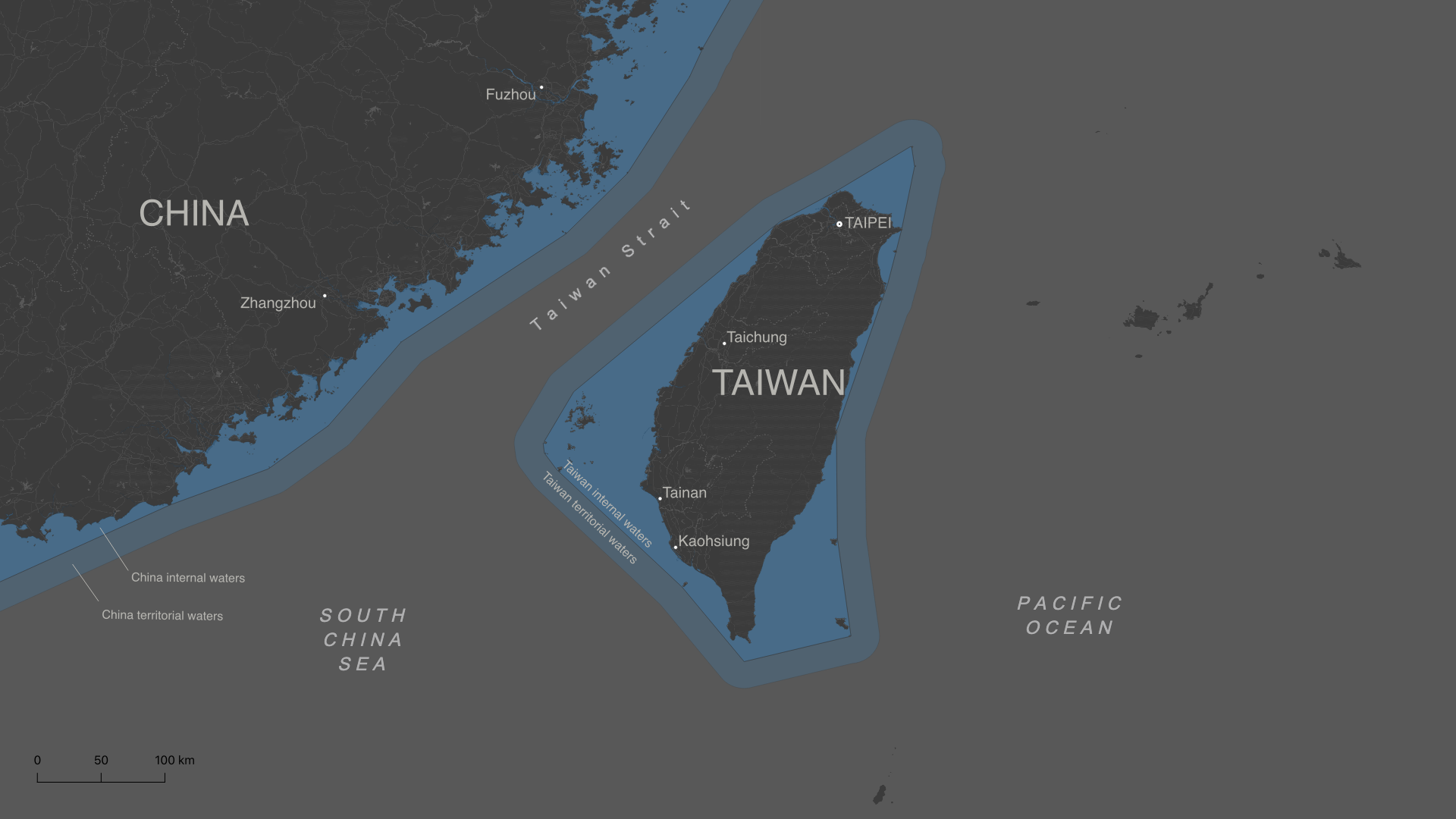

Taiwan is located in the South China Sea, less than 150 km from Fujian Province in

mainland China.

The Taiwan Strait separates the two territories.

The strait is one of the world's major maritime trade routes, connecting China,

Japan, Korea and Taiwan with Europe and the United States.

Some 48% of all the

world's container ships sailed through it so far in 2022, according to Bloomberg data.

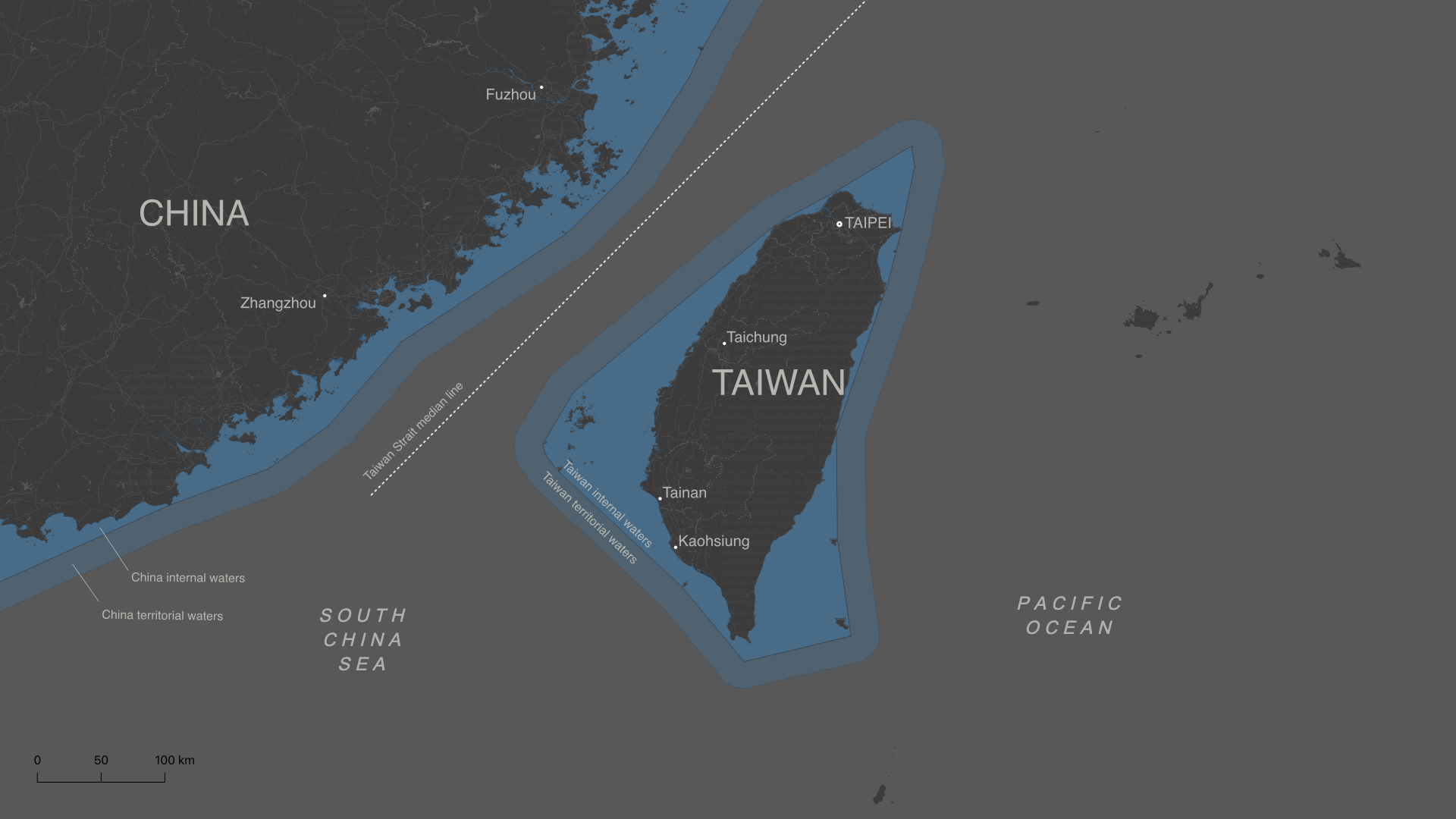

The median line was historically the unofficial demarcation of the two sides of the

Strait.

China does not recognise this line and since the late 1990s its military

aircraft began crossing it.

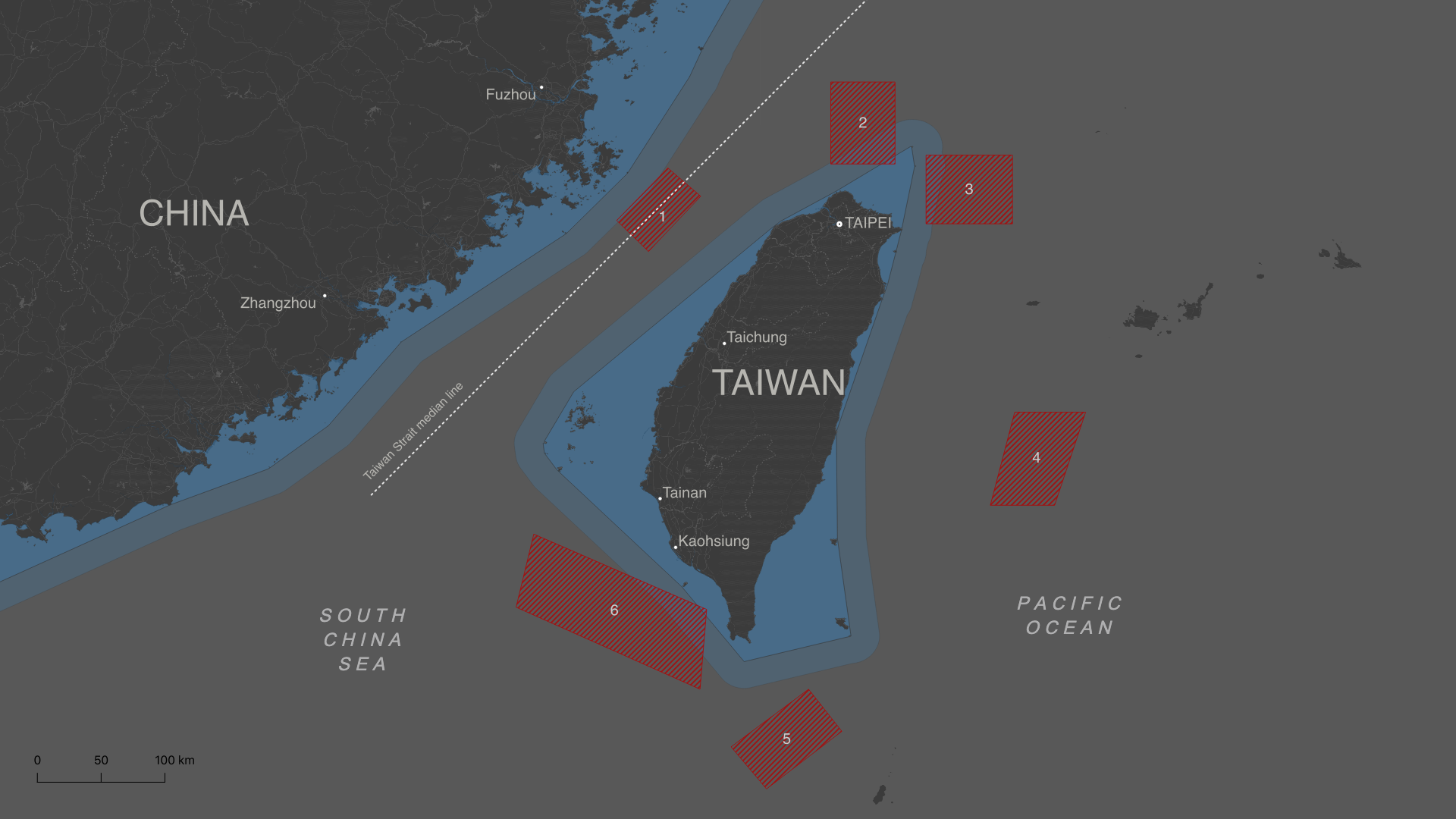

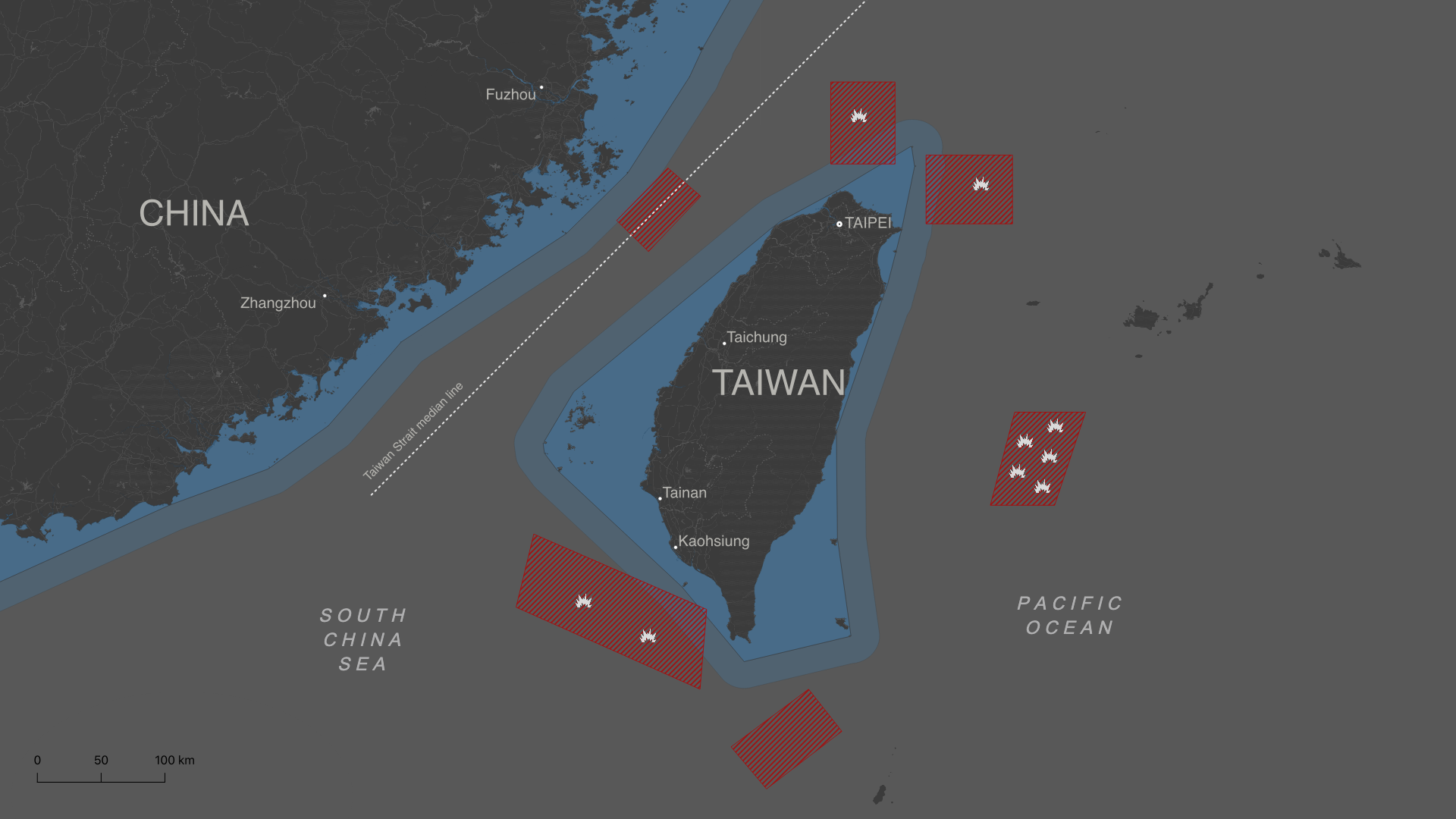

On 4 August, following Pelosi's visit, China began military exercises in six zones beyond

the median line.

Drill zones 2, 3 and 6 are in waters that Taiwan recognises as its own, less than 20 km

from the island.

Japan's Ministry of Defence detected the launching of 9 missiles into the sea from mainland

China.

On their trajectory, some of them overflew Taiwan.

The Chinese military exercises began on 4 August at 4:00 UTC and were initially scheduled to end on 7 August at 4:00 UTC, according to China's official Xinhua news agency. But they were eventually extended until the 10th.

China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) deployed more than 100 aircraft, an undetermined number of vessels, and launched more than 10 missiles, conducting operations "of joint blockade, assault on ground and sea targets, airspace control, joint anti-submarine drill, and integrated logistics and support".

The last time China had conducted military exercises on this scale in the area was between 1995 and 1996.

Impact on maritime traffic

As part of its activities, Beijing banned all ships and aircraft from entering the designated areas, causing delays and increased costs for maritime traffic.

Some companies decided to reroute their ships to Taiwan's east coast to avoid the Strait - which involves three extra sailing days - and others postponed loading their cargoes until the following week to avoid risks, according to Bloomberg.

"There is potential for substantial disruption to trade in the region," told to CNN Business Peter Williams, an analyst at VesselsValue, a consultancy that monitors global shipping traffic. According to VesselsValue, there were more than 300 container ships in Taiwanese waters during the drills.

All-seeing eyes from the sky

Usually, ships can be located thanks to the automatic identification system (AIS), the system by which they transmit their position to each other in order to avoid collisions. This is what platforms such as MarineTraffic use to display real-time maritime traffic.

But by simply turning off their transponders, any vessel can disappear from the positioning systems.

There are many reasons to go dark: to hide an illegal act such as fishing in prohibited waters or smuggling, to avoid sanctions, or because they are on a military mission.

This is where satellite imagery can provide valuable information: no ship can avoid being spotted from the sky.

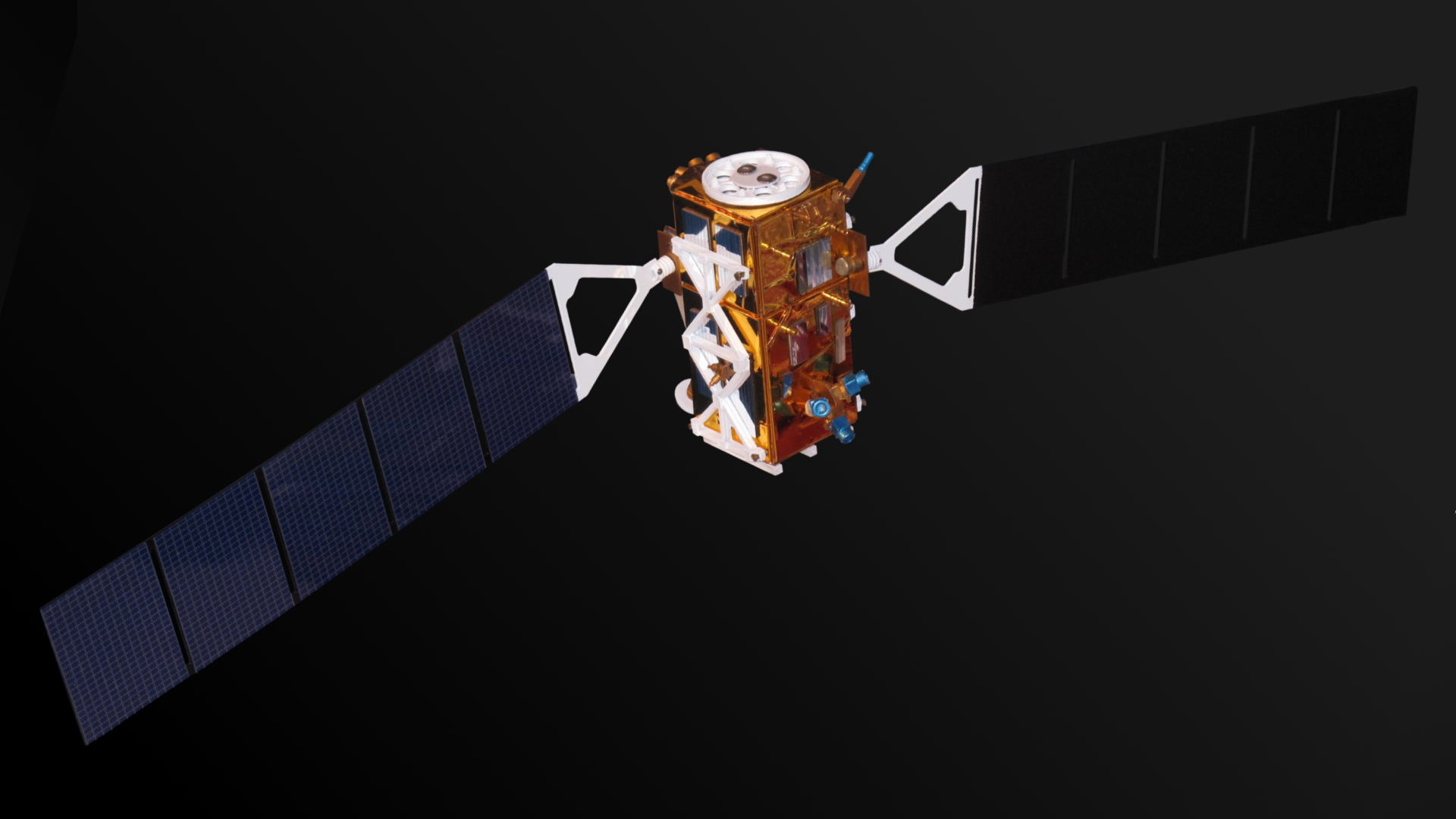

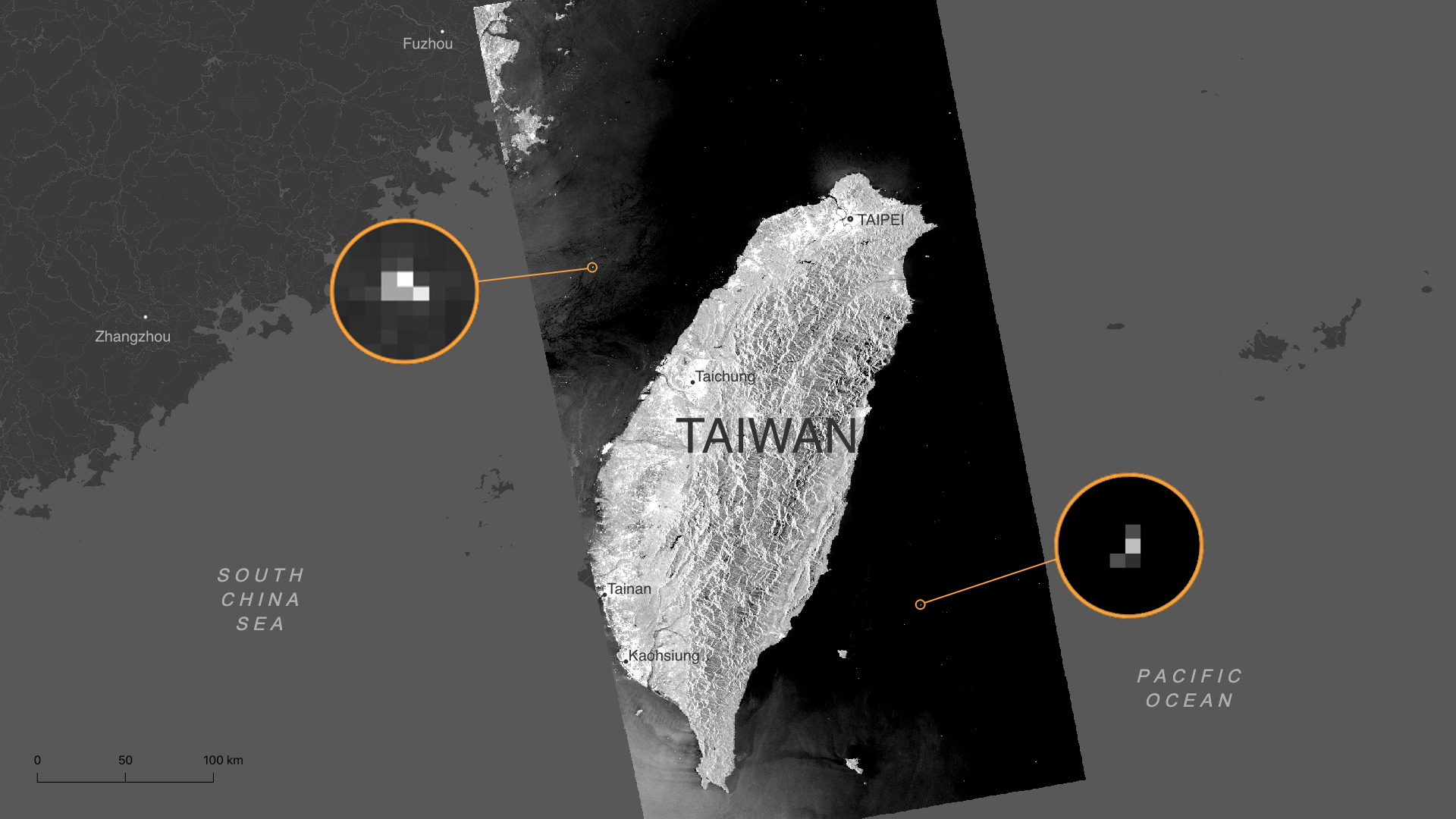

Sentinel-1 is a European Space Agency (ESA) mission consisting of two satellites equipped with Synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) to take images of the Earth.

Every 12 days, the satellites re-image exactly the same place on the planet.

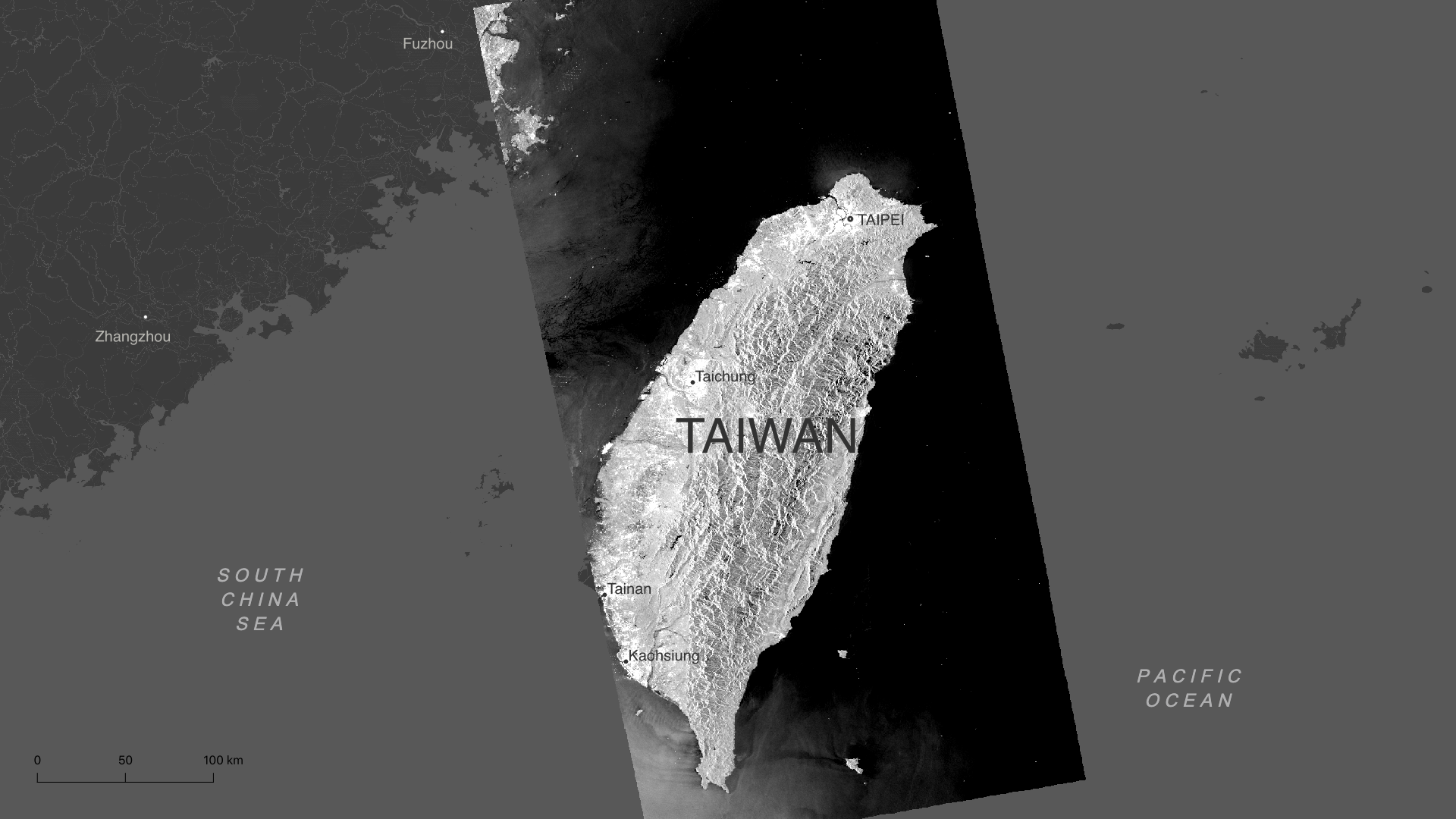

On 5 August at 10:01 UTC, 30 hours after the start of the Chinese military exercises, Sentinel-1 flew over Taiwan.

This is the radar image it captured.

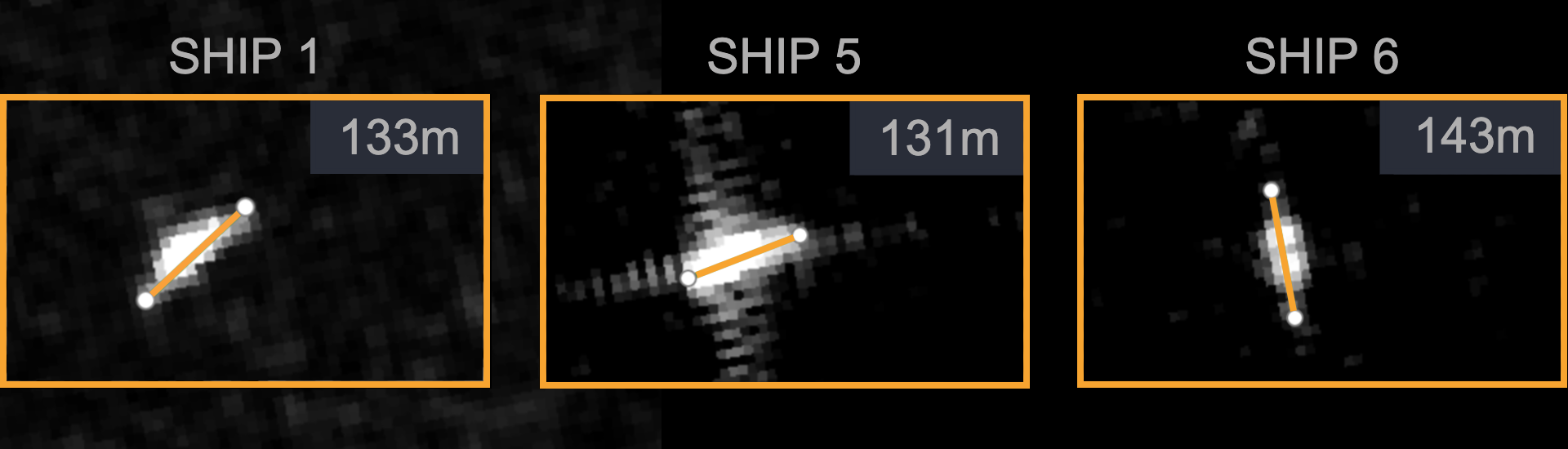

The image was processed with an algorithm to detect all ships that were 30 metres or more in length or width.

The algorithm spotted 2076 ships...

...of which almost 10% (196) were very large ships, 30,000 square metres or more in area.

These are mostly container ships, bulk carriers and tankers, which are essential for international supply chains.

In search of safer waters

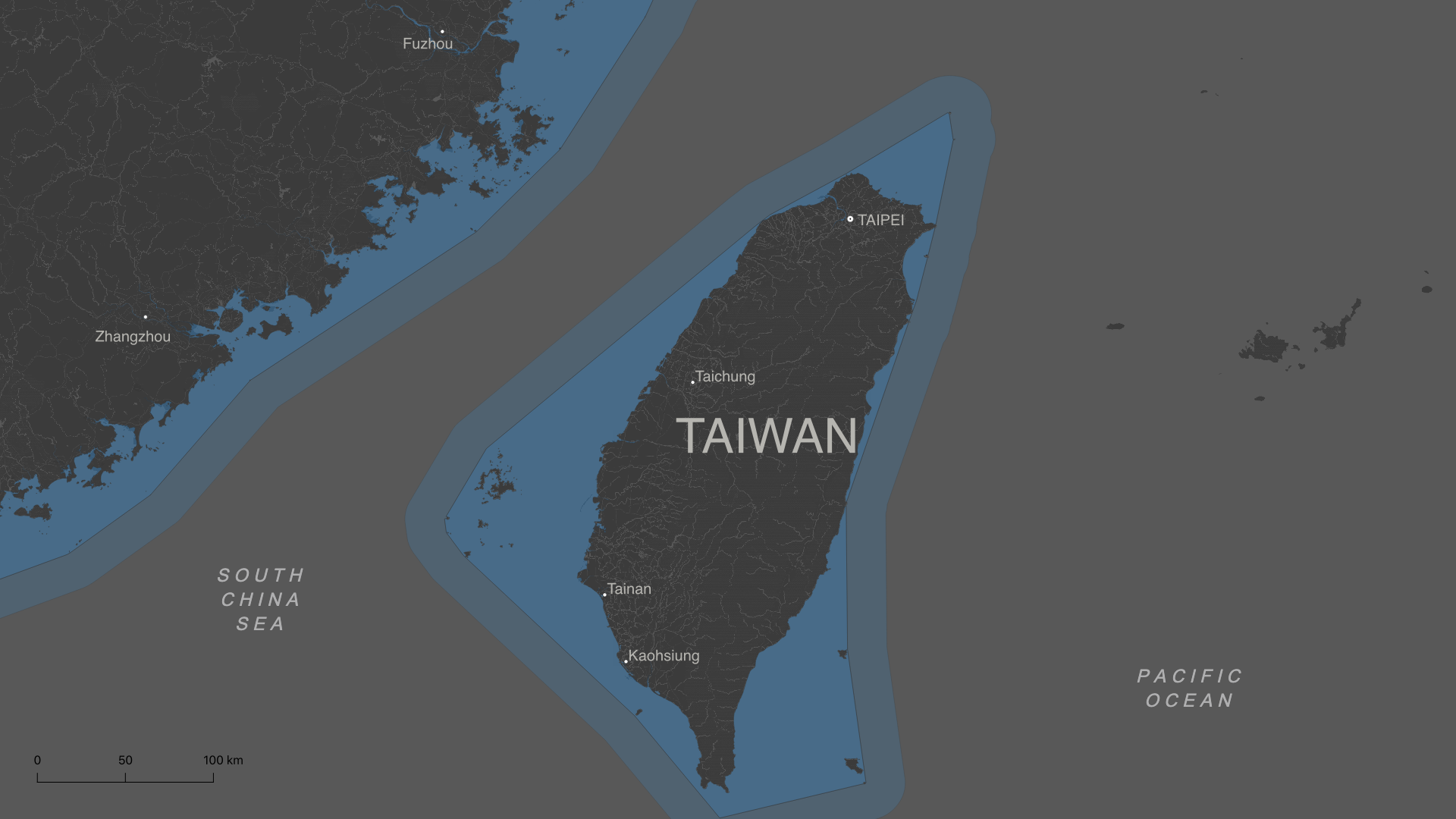

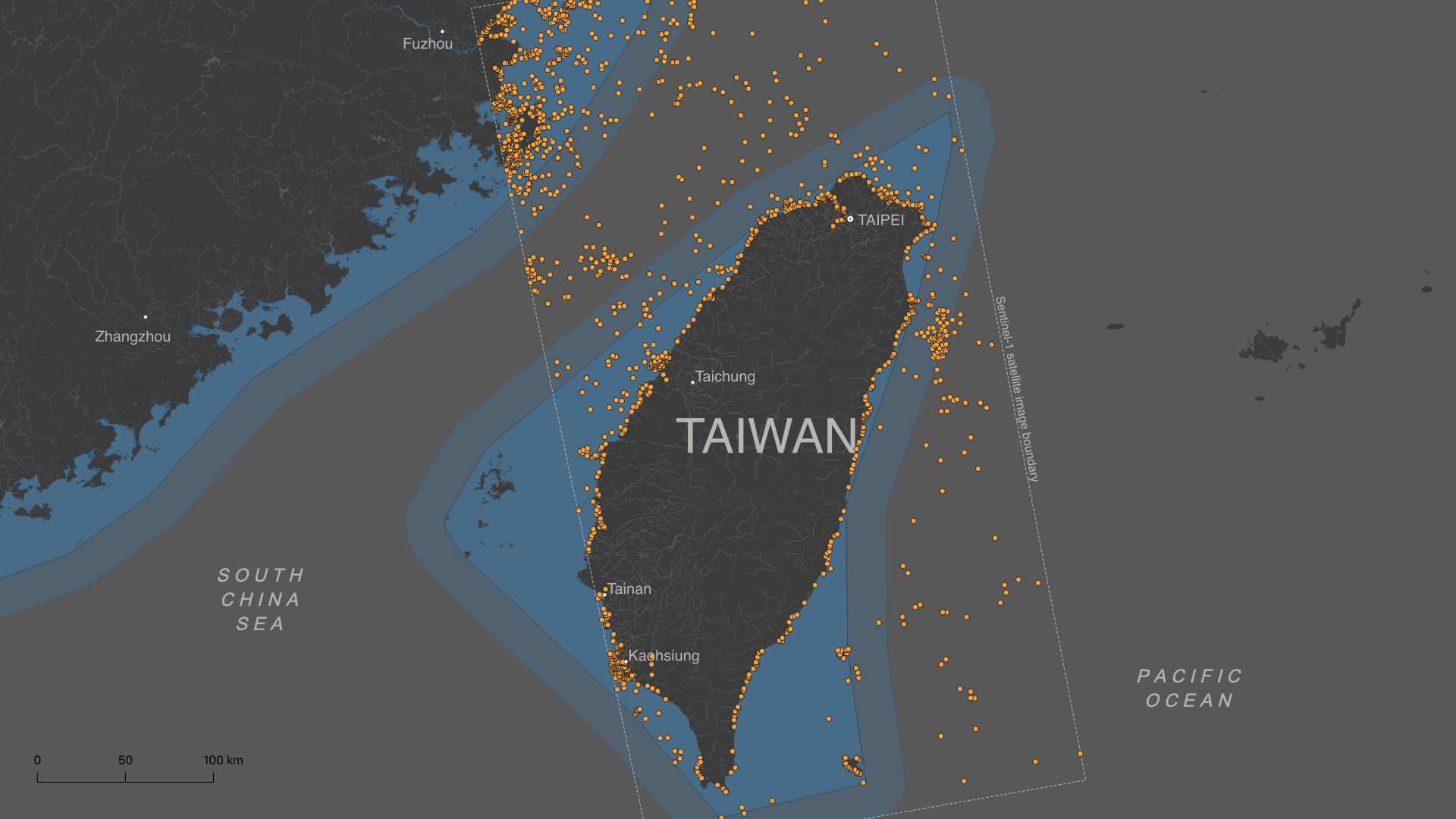

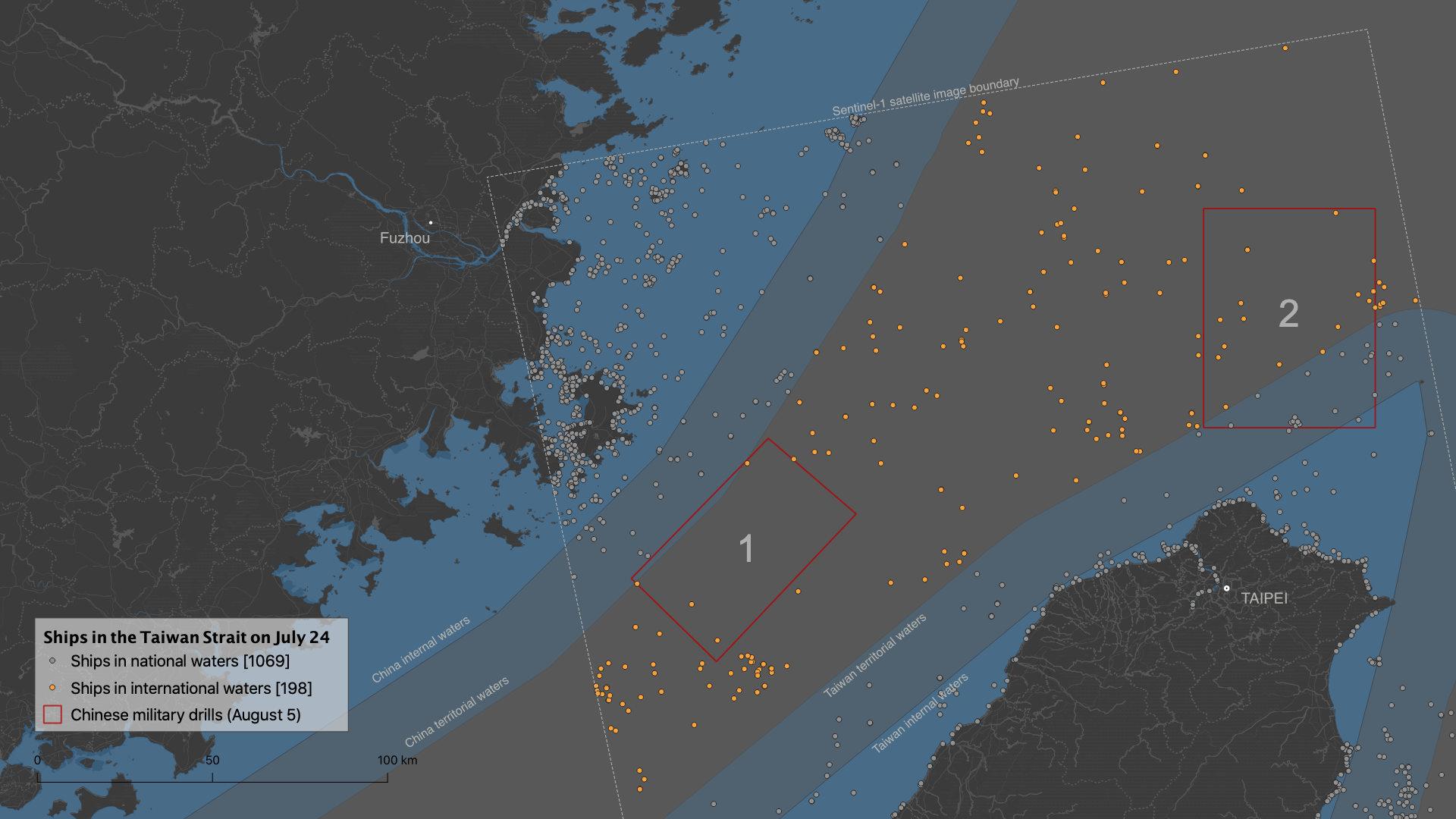

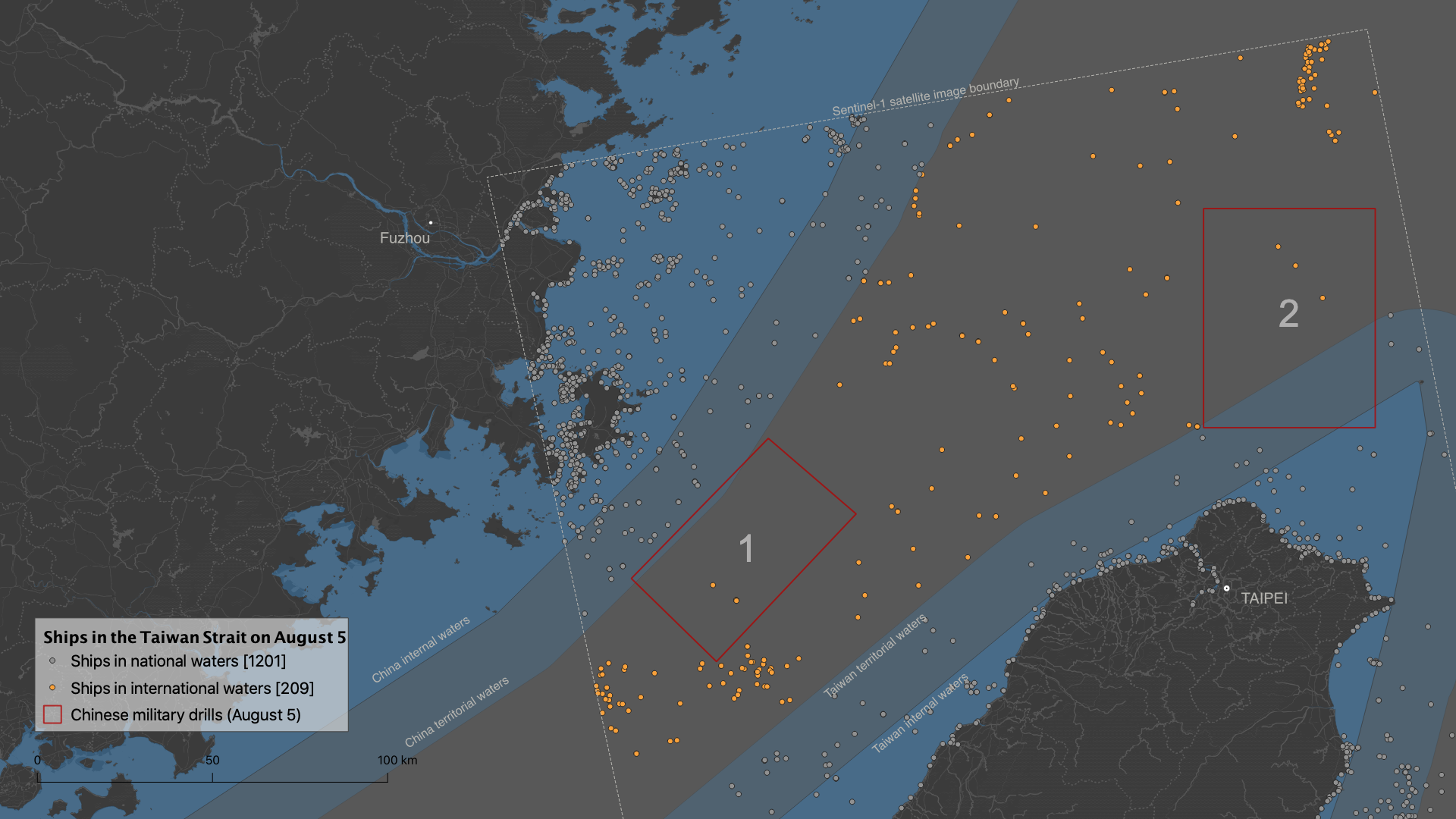

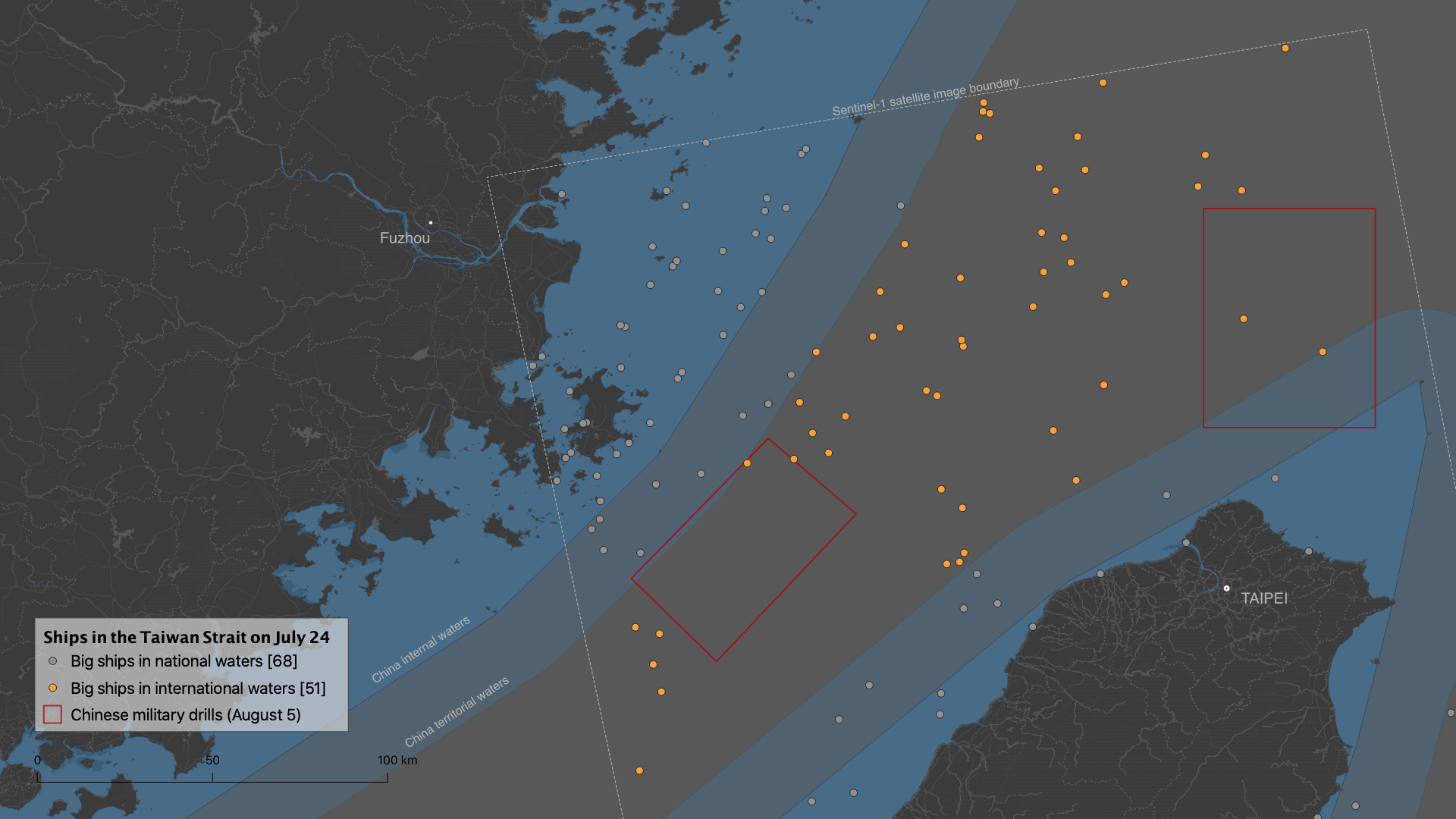

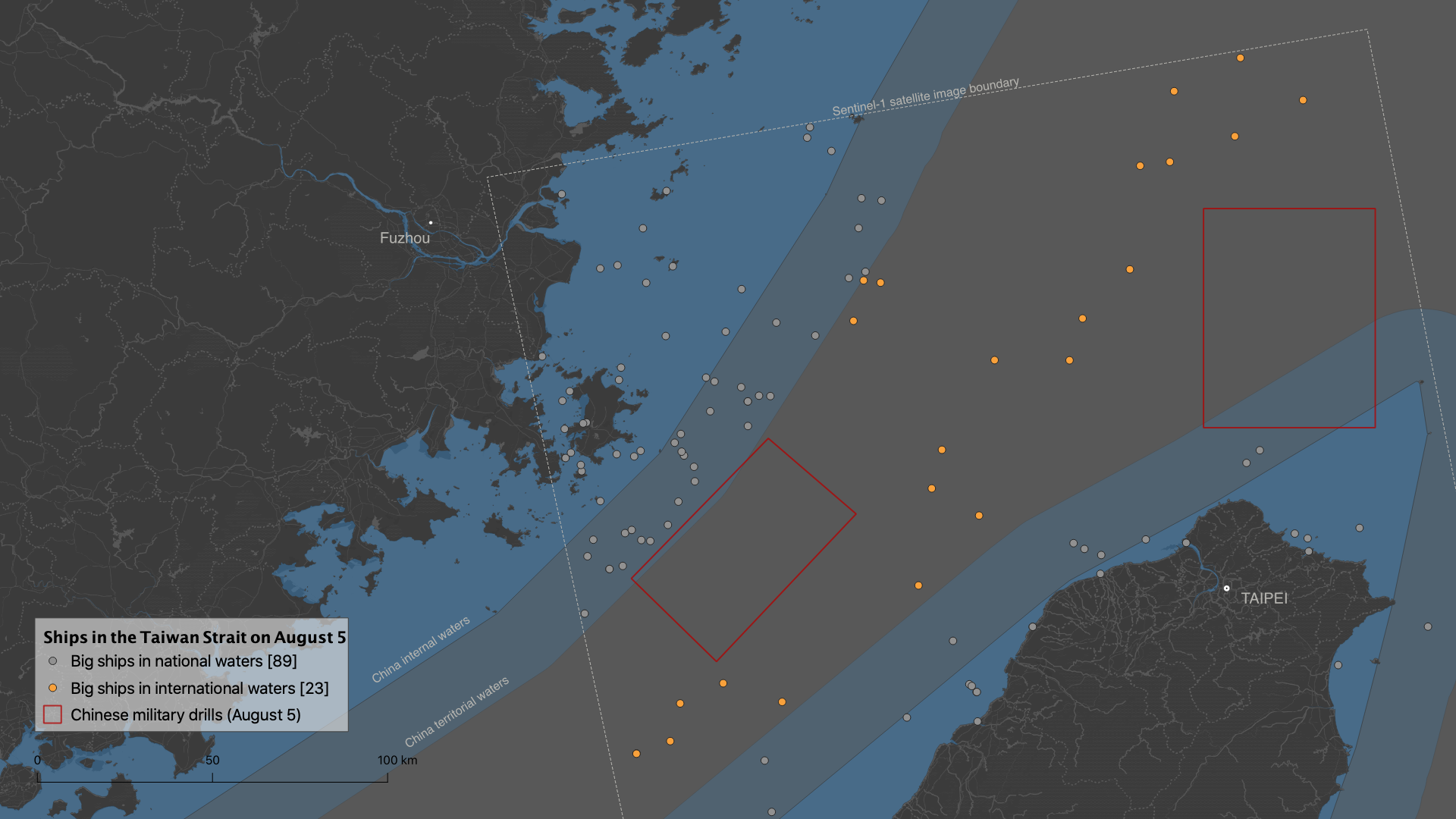

To understand how maritime traffic was impacted, I analysed Sentinel-1 images from the same location but on different dates, focusing on the northern Taiwan Strait, where Chinese forces began military exercises from 4 August in two areas.

This meant blocking almost 50% of the width of the Strait's international waters.

The images analysed are 12 days apart, on 24 July and 5 August, and were taken by Sentinel-1 at the same exact time (10:01 UTC). On both days there were good weather conditions for navigation, therefore the differences found aren't due to the weather.

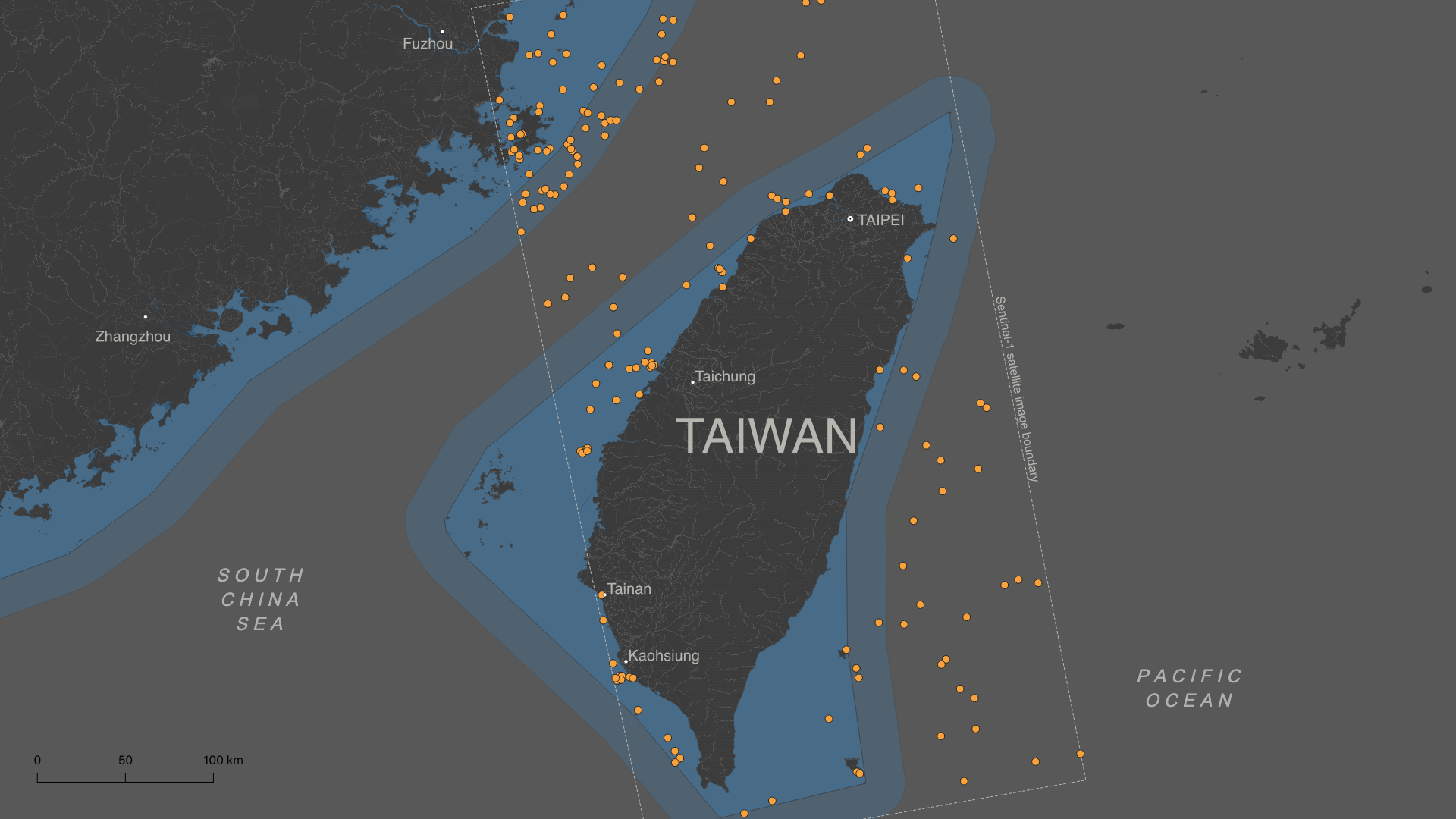

When comparing the ships detected in both images, it is clear that at the start of the military exercises the container ships and tankers abandoned their usual route through the centre of the strait, moving towards safer waters.

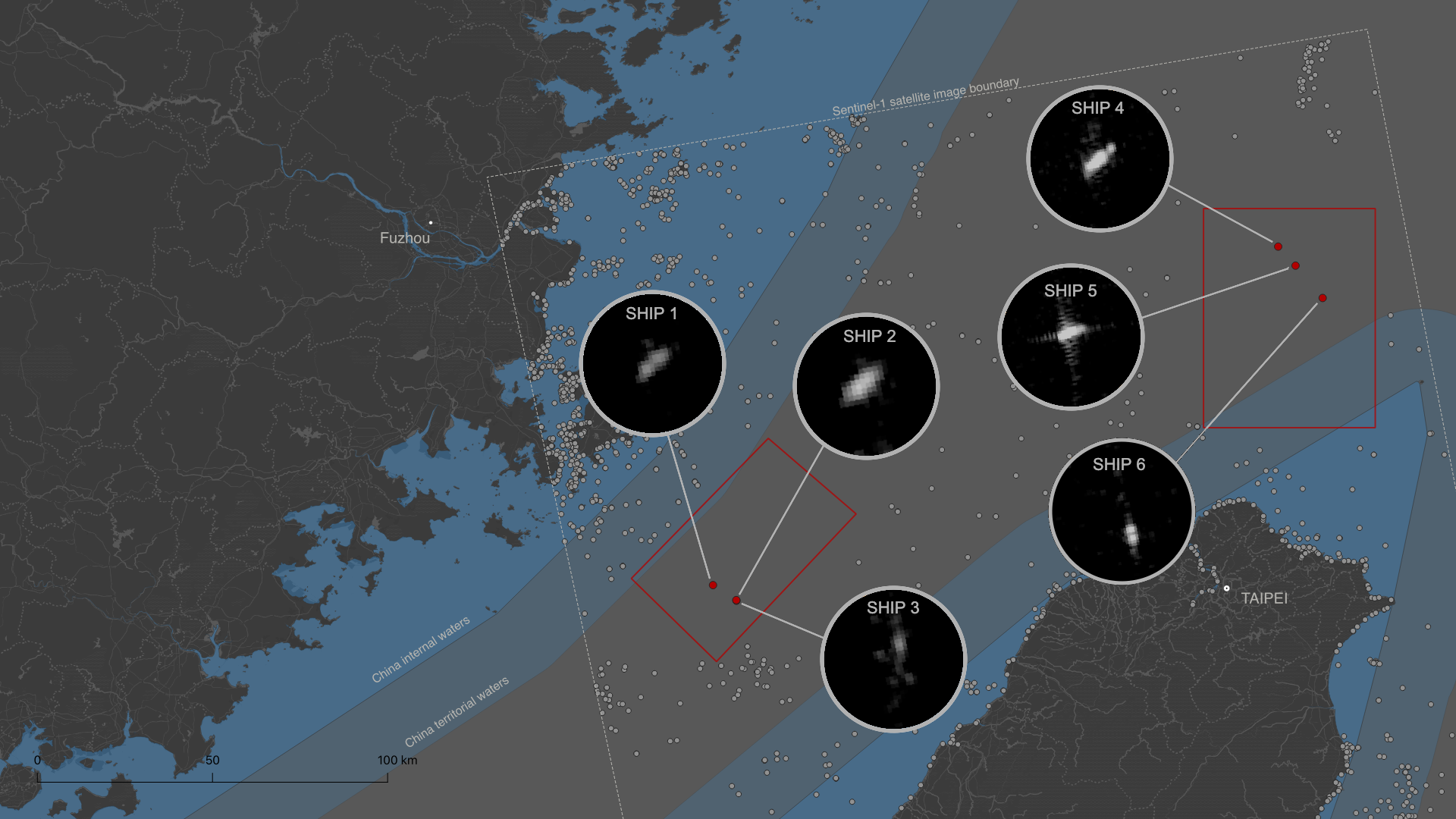

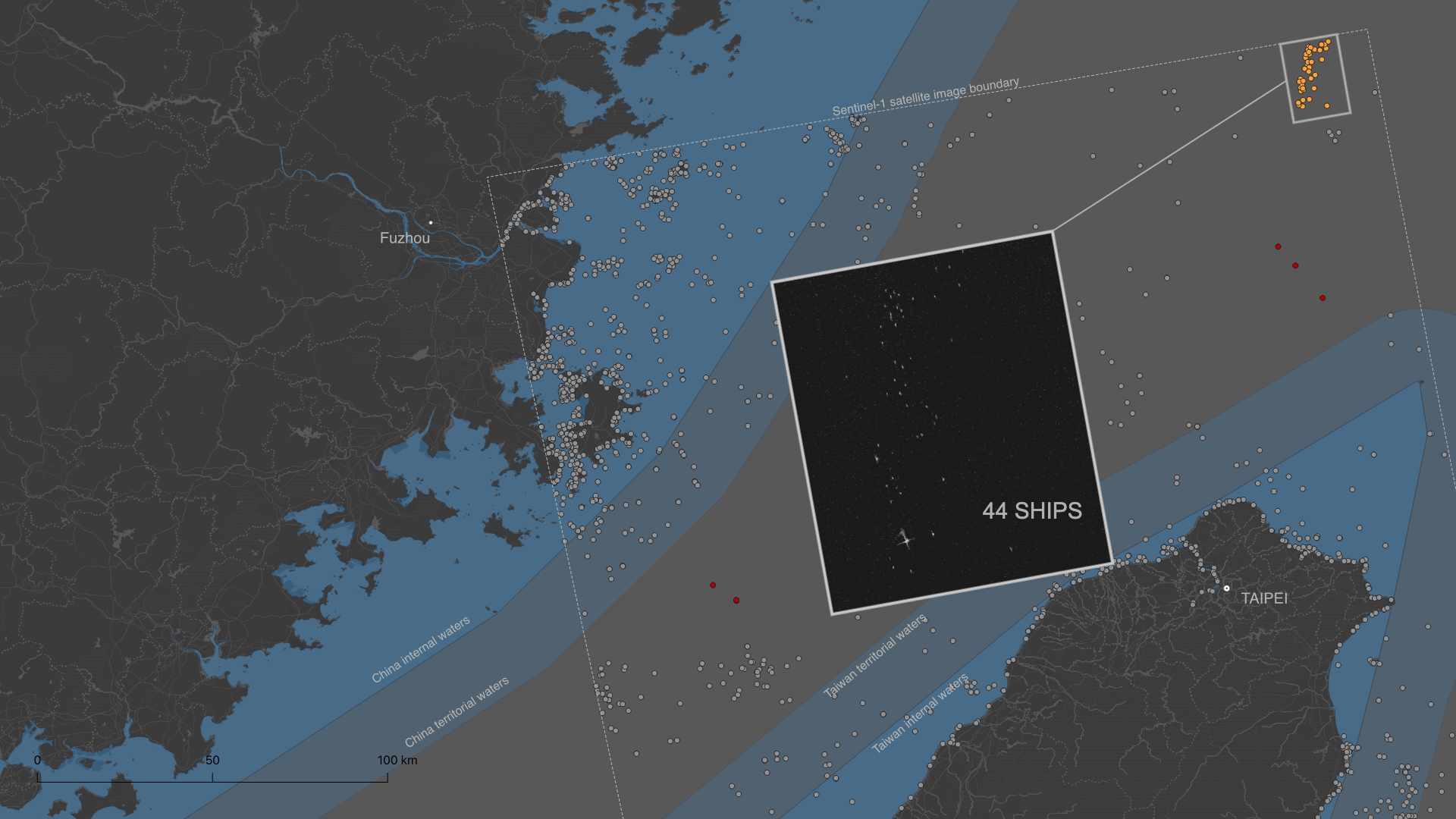

The algorithm also revealed the possible location of some of the military ships involved in the operation and a remarkable concentration of vessels in a small area.

On 24 July, there were 1,267 ships north of Taiwan, 15% of which were in international waters.

In Areas 1 and 2, which a few days later would be the scene of military exercises, traffic was normal.

On 5 August, with Chinese forces already deployed, it was a different story.

There were 1410 ships, 16% of which were in international waters. But now the vast majority of them were avoiding the red zones.

The algorithm detected at least six ships in the restricted sectors.

Given their

position, it is very likely that they are Chinese military vessels.

To the northeast, at the edge of the Sentinel-1 image, there is an unusual concentration of 44 ships in a small area that was not present at the previous date.

If only the large ships are considered, the impact of the military exercises was even

greater.

On 24 July, 51 of the 119 large ships present were sailing in

international waters in the Strait....

...but by 5 August, only 23 of 112 large ships were still there, a drop of more than

50%.

The vast majority had diverted to Chinese or Taiwanese territorial waters in

search of safety.

Is it possible to identify a military vessel?

By cross-referencing the Sentinel-1 image with official Chinese sources, it is possible to obtain some more data.

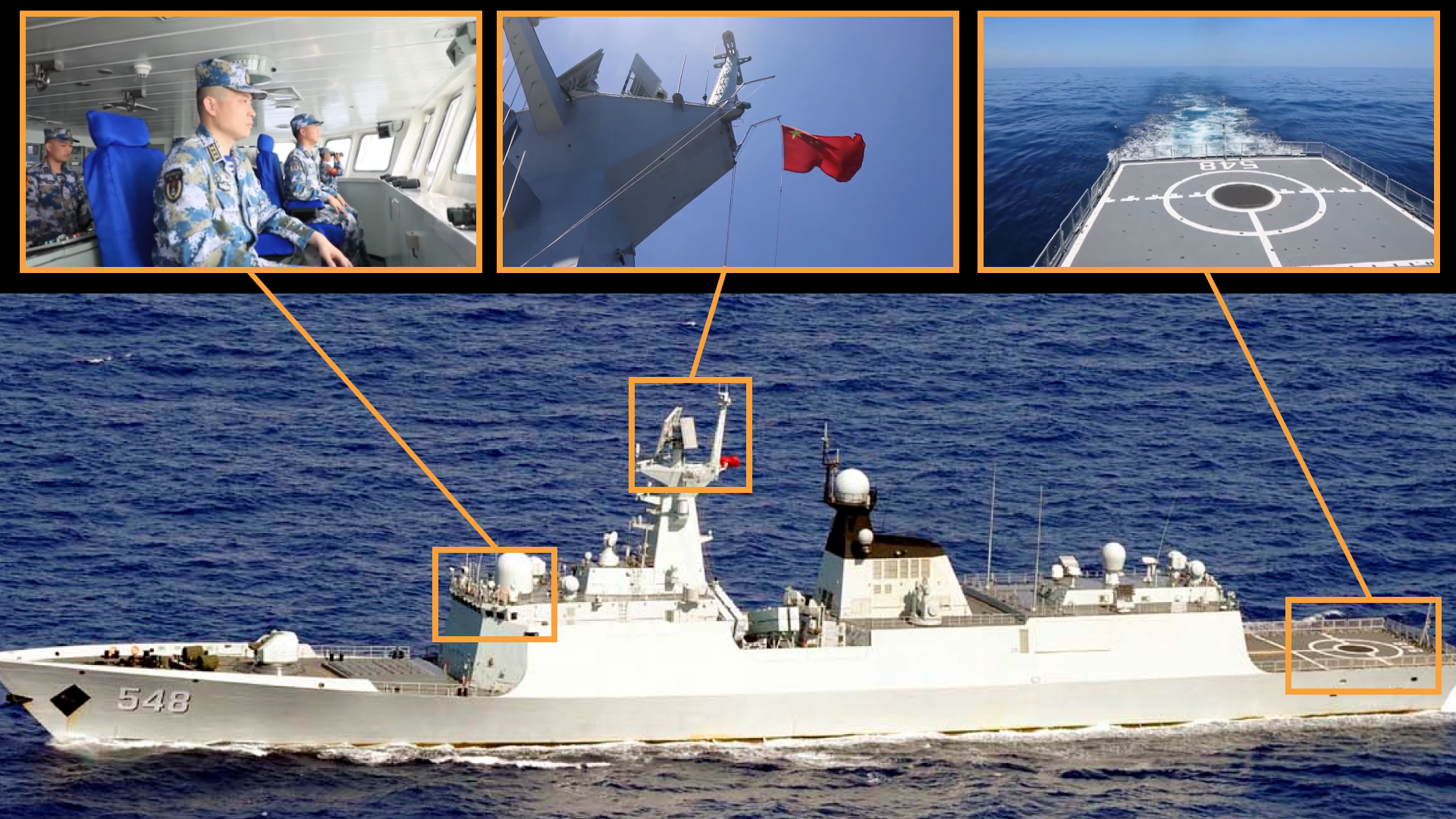

On 6 August, the Xinhua news agency published some reports on the activities of the previous day, when Sentinel-1 captured the radar image. Among them is a video of a ship in action that appears to be the Yiyang (548) , a Type 054A frigate of the Chinese forces.

The image below compares three screenshots from that video with an image of the Yiyang (548) released in 2013 by the Japanese Ministry of Defence, which allows to verify that it is the same ship.

As the Yiyang (548) is 134.1 metres long and 16 metres wide, it could well be ship 1, 5 or 6 identified by the algorithm in the military exercise areas. The resolution of the Sentinel-1 SAR image is 10m per pixel, so the measurements made have an estimate of ± 10m.

Ships 2, 3 and 4, on the other hand, are either too large or too small to be the Yiyang (548).

It should be noted that the ship detection algorithm was only applied to military exercise zones 1 and 2, so the Yiyang (548) could have been sailing in another sector at the time of Sentinel-1's overflight.

China has several Type 054A frigates, all of the same size, which may also have participated in the exercises and may be one or more of the ships detected. Finally, the video published may have been recorded on a different day, so it cannot be reliably verified that the Yiyang (548) was there either.

But beyond its limitations, this methodology, complemented by other sources of information, may help to identify some of the units used in the military operation.

* * *