Farewell to the forest

Hundreds of hectares of forest are destroyed every year in northern Argentina, despite

being protected by law.

This is a map of that destruction.

By Federico Acosta Rainis

Between 2000 and 2007, driven by rising commodity prices, Argentina increased its cultivated area by 21%, from 24.3 to 29.5 million hectares, according to official data. This is more than the size of Slovakia.

The crop that saw the biggest increase was soy, up 63%, from 7.8 to 12.7 million cultivated hectares.

How did this happen so quicly?

Mainly by indiscriminate logging, taking advantage of the lack of legislation.

After years of pressure from environmental organisations and civil groups, in 2007 Argentina finally passed its national Forestry Law to halt the destruction of its native forests.

An analysis of satellite data shows, however, that fifteen years after this law, destruction has slowed but not stopped.

The never-ending logging

According to the 2020 State of the Environment Report published by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, between 1998 and 2020, Argentina lost 6.9 of its 54.3 million hectares of native forests, 13% of the total.

"Deforestation contributes to the climate crisis and makes us more vulnerable. One hectare of forest absorbs 100 times more water than one hectare of soy," says Hernán Giardini, coordinator of Greenpeace Argentina's forests campaign.

"Studies show that the loss of forest brings desertification, salinisation and the temperature of the area can rise up to two or three degrees."

The 2007 Forestry Law established three categories of native forests:

- Category I (red): cannot be exploited.

- Category II (yellow): cannot be cleared and can only be used sustainably, for tourism, gathering or scientific research.

- Category III (green): can be partially or totally transformed.

Local classification was entrusted to each of the 23 provincial governments, together with the obligation to update this territorial register every five years.

In practice, very few provinces complied: only in 2016 all completed the initial categorisation and by 2020 only five had complied with the first mandatory update.

A broken law

Despite the new law, deforestation remained particularly strong in the north, in the provinces of Chaco, Salta, Formosa and Santiago del Estero.

From 2008 onwards, 85% of the country's forest loss occurred in these provinces, in the Gran Chaco forest. It is the second largest forest in Latin America after the Amazon, covering part of Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil for some 650,000 km2.

"The Gran Chaco forest provides food and medicine and is large reservoir of biodiversity, starting with large mammals, such as the tapir, the anteater and the jaguar," says Giardini.

The jaguar, the largest feline in the Americas, is on the verge of extinction and it is estimated that there are only 20 specimens left in the area. To survive, each of them needs at least 40,000 hectares of healthy forest.

This year, the Supreme Court of Justice accepted a lawsuit filed in favour of the jaguar against the provinces of Chaco, Salta, Formosa and Santiago del Estero.

This is a historic milestone, as there is no precedent of the highest court accepting a similar kind of lawsuit.

The situation in Chaco Province

According to official data, between 2007 and 2020 the Chaco Province (named after the forest itself) lost a monumental half a million hectares of forest.

Giardini argues that with the Forestry Law, state control has increased, but it is still low.

"The fines are not enough to deter illegal logging: when they are very low, the offenders pay them. And when they are high, they prefer to go to court, which takes many years, while they continue to exploit the land," he says.

Environmental organisations such as FARN have reported that in recent years the Chaco government has authorised dozens of individual re-categorisations to allow logging, downgrading areas that were originally protected from yellow to green.

This goes against the original spirit of the Forestry Law: according to the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, re-categorisations "should only be granted for exceptional cases and never be of general and systematic application".

In October 2020, in fact, a Chaco court suspended all land clearing and land use changes made since 2014, when the province should have updated its protected areas register but failed to do so.

But the illegal logging goes on and on.

Mapping the lost forests

In the last year alone, some 7,200 hectares of protected forests have been cleared in the north of Chaco province.

This is the equivalent of more than 10,000 football pitches - some 28 football pitches per day - and over a third of the size of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina's capital.

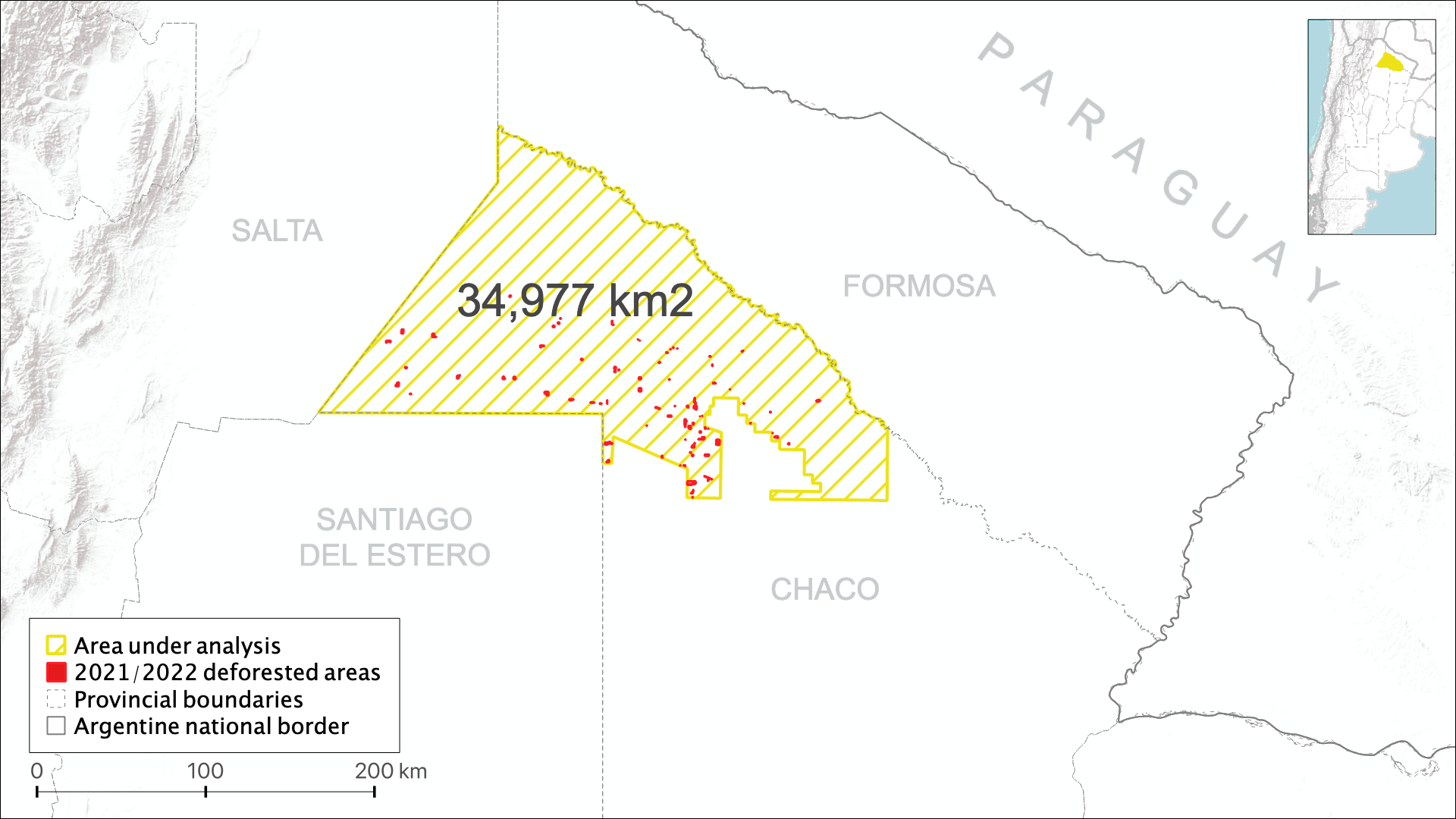

The data comes from an analysis of satellite images of June 2021 and June 2022 processed by an algorithm that helped identify land-use changes in an area of almost 35,000 km2, where deforestation is forbidden.

Map created by Federico Acosta Rainis | Basemap tiles by Esri.

The following interactive map shows in detail the changes over the last twelve months. The methodology and code used are available here.

On the left side the region is shown as photographed by ESA's Sentinel-2 mission throughout May and June 2021. On the right, the images are from June 2022 and the new 113 deforested patches are marked in red.

The average size of each deforested patch is 64 ha, while the largest area deforested in a single patch is 370 ha.

Use the slider and zoom in to compare the before and after of each patch of lost forest.

NOTE: the map uses a very large number of images, so it may take a few seconds to load all the layers.

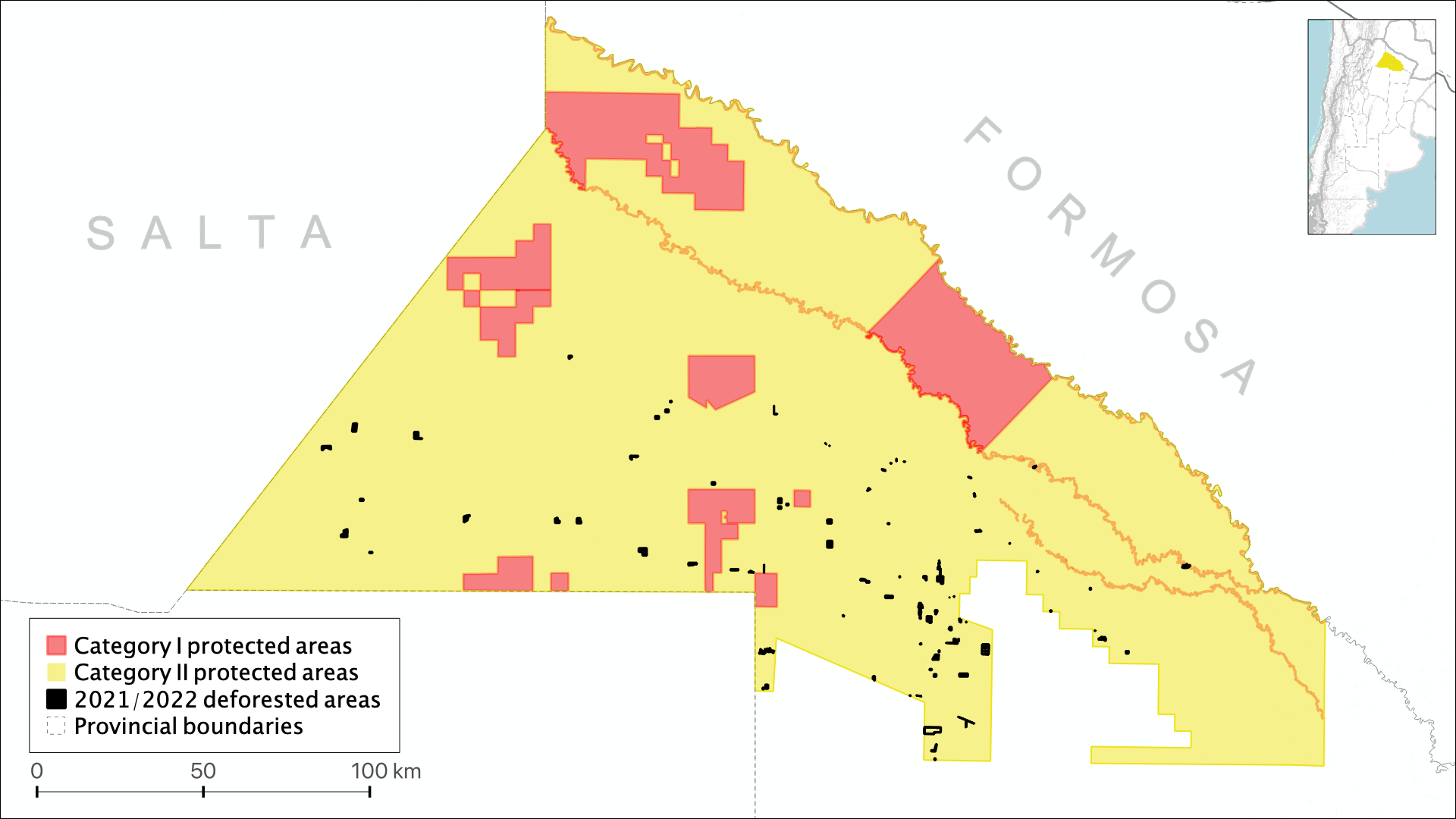

Yellow... but almost red

The algorithm didn't detect any forest loss in category I areas, but some deforestations occurred in category II areas very close to the category I boundary.

Map created by Federico Acosta Rainis | Basemap tiles by Esri.

A patch of about 70 hectares of native forest was cleared just 1.3 km from the Loro Hablador Provincial Park, one of Chaco's most important flora and fauna reserves.

Three other areas were cleared within metres of the Bermejito River, despite the fact that the law prohibits deforestation in any area within 30 metres of its banks.

The future of Gran Chaco

Some of the most typical trees of the Gran Chaco are hardwood and slow-growing, such as quebracho and algarrobo. According to Giardini, a moderately degraded forest takes at least forty years to recover.

The activist believes there is still time to save it, but action must be taken immediately. And that the key lies in the new generations.

"There is an interesting mobilisation of part of the society that lives in the cities, especially young people, who are very concerned about the environmental issue and can put pressure on governments."

He also believes that Argentina does not need to continue deforesting in order to develop. On the contrary.

"After 30 years of deforestation, Chaco is still one of the poorest provinces in the country. How much has the quality of life of these people improved after having devastated this territory?"

"We must take on this climate emergency now. If we do nothing, the future will be terrible."

* * *

Bonus track: how does the algorithm detect deforestation?

To identify deforestation, I used a machine learning algorithm called Random Forest (RF) to perform what is called a supervised classification. The name of the algorithm has nothing to do with its usefulness for detecting forests: it is named after the way it processes data, building "decision trees".

First I manually categorised different land uses (water, crops, forest, low vegetation and deforestation) at many points in a satellite image. I then fed this information to the algorithm, so that it could learn to distinguish the categories on its own and replicate the classification for the entire northern Chaco.

For more information, scope and limitations and access to the source code, see Methodology.

The following figure compares the original satellite images and the classification performed by the algorithm in both periods to show how it works.

* * *